The Knight Family have lived on the estate of Chawton since 1524. Four generations on Elizabeth Knight, whose portrait can be seen in the Great Gallery, made her cousin Thomas May her heir. Thomas May, taking the name Knight united the properties of Chawton and Godmersham Park in Kent. Both houses had libraries and the current Knight Collection now holds what remains.

Thomas Knight’s son, also Thomas, adopted Edward Austen, again a cousin, as his heir. The arrival of Jane Austen in the village in 1809 happened because Edward Austen Knight provided a home in the Bailiff’s Cottage. His son, also Edward, made his home at Chawton from 1826 and Godmersham Park was sold in 1874.The main collection contains a sales catalogue of the estate, and the contents of the library at Godmersham were moved to Chawton House. The holdings of the Godmersham Park Library were recorded in 1818 in the surviving two volume manuscript catalogue, which gives us some idea of the books moved to Chawton after the sale of Godmersham.

Edward died a few years later in 1879 and his son Montagu, inherited Chawton Park. Montagu Knight had a catalogue compiled for the library at Chawton House in 1908 and currently the existing Knight Collection is being catalogued.

The current owner, Richard Knight, inherited the collection in 1989 and no changes have been made to it since then, so with the documentary evidence we have about the family holdings we will in time reconstruct the development, changes and dispersals of a family’s collection over several generations between 1818 and 1989.

This long-term project includes the Bibles held in the Knight Collection at Chawton House Library which date back to before the King James Bible was completed in 1611. It is pertinent at the point where 400 years of the King James Bible is being celebrated to look at one family’s relationship with religion using some of the evidence we have.

William Tyndale produced the first printed translation of the New Testament in English in 1525. The official Great Bible of 1539, with a preface picturing Henry VIII, was intended for reading aloud in churches and it re-used much of Tyndale's work. In 1557 the Geneva (Calvinist) New Testament in English was published, followed in 1560 by the complete Geneva Bible. This was superseded in England in 1568 by the official Bishops' Bible, although the Geneva Bible was still widely used. Then in 1601, there was the new initiative in Scotland which led to the production of the King James Bible in 1611. By about 1900 the language of the King James Bible was seen as increasingly archaic and many other versions have been produced, including the New English Bible, amongst many others, but also one we are familiar with now.

So far I have collated the following list of the bibles in the Knight Collection:

1. Hole, W. (ill.) (1909?) The New Testament of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ: translated out of the original Greek: and with the former translations diligently compared and revised by His Majesty's special command .London: Eyre & Spottiswoode. [Accession no. 9471] Illustrated and containing prayer cards.

2. The New English Bible: New Testament (1961). Oxford: Oxford University Press; Cambridge University Press. [Accession no. 9482]

3. The New English Bible: New Testament (1961). Oxford: Oxford University Press; Cambridge University Press. [Accession no. 9469] This Bible is dedicated to ‘Anne from Hylda Bannister with many happy memories of Hall Dene School, Alton, and best wishes for a very lovely life in the future’.

4. The Holy Bible containing the Old and New Testament; translated out of the original tongues: being the version set forth A.D. 1611 compared with the most ancient authorities and revised (1960). London: The British and Foreign Bible Society. [Accession no. 9483] Inscribed ‘Anne Knight’ with lists of bible readings.

5. The Holy Bible containing the Old and New Testament / translated out of the original tongues and with the former translations diligently compared and revised by His Majesty’s special command; appointed to be read in churches; Authorized King James version; printed by authority (1957). London & New York: Collins’ Clear-Type Press. [Accession no. 9475] inscribed ‘Anne Knight’ and containing a prayer card.

6. The Holy Bible - containing the Old and New Testament translated out of the original tongues and with the former translations diligently compared and revised, by His Majesty’s special command; appointed to be read in churches (1938). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Accession no. 9467]

7. Leusden, J. and Hooght, E.v.d. (eds.) (1831) Biblia Hebraica, secundum ultimam editionem jos. athiae a Johanna Leusden...ab Everado van der Hoght, V. D. M. Editio nova, recognita, et emendata, a Judah D'Allemand. Londini: Typie excudabat A. Macintosh, 20 Great New Street. Impensis Jacobi Duncan, Paternoster Row. [Accession no. 9478] Inside the front board is the stamp of Adela Portal, and inside the back board the bookplate of her son, Montagu Knight.

8. The Holy Bible containing the Old and New Testament: translated out of the original tongues: and with the former translations diligently compared and revised / by His Majesty’s special command. Appointed to be read in churches; Authorized King James version; printed by authority (1929). Oxford: Printed at the University Press, for the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. [Accession no. 9481] Contains two black and white bookplates for P. A. Knight of a type , one is Peter Rabbit, that suggests ownership by a child.

9. The child’s Bible being a consecutive arrangement of the narrative and other portions of holy scripture in the words of the authorized version: with upwards of two hundred original illustrations (1897). London: Cassell and Company Limited. [Accession no. 9470]

10. The annotated paragraph Bible: containing the Old and New Testaments, arranged in paragraphs and parallelisms; with explanatory notes, prefaces to the several books, and an entirely new selection of references to parallel and illustrative passages. The Old Testament. (1864). London: The Religious Tract Society. [Accession no. 9472] This bible is that of C.E. Knight (Charles Edward Knight) who was a younger son of Edward Austen Knight and lists the details of his family’s births and deaths from 1846-1918.

11. Scott, T. (ed.) (1850) The Holy Bible; containing the Old and new Testaments, according to the authorized version; with explanatory notes, practical observations, and copious marginal references / by the late Rev. Thomas Scott... a new edition, with the authors last corrections and improvements, and eighty-four illustrative maps and engravings. [New edn.] London: Printed for Messrs. Seeleys, Fleet-Street and Hanover-Street; Hatchard and Co., Piccadilly; and Nisbet and Co., Berners-Street. [Accession no. 9473]

12. The Holy Bible, containing the Old and New Testaments: translated out of the original tongues: and with the former translations diligently compared and revised / by his Majesty's special command. Appointed to be read in churches. (1841). Oxford: Printed at the University Press, by Samuel Collingwood and Co. printers to the University; for the Society for promoting Christian Knowledge. [Accession no. 9484] There are a set of bibles, differing slightly in size but bound similarly, this one is inscribed ‘Chawton Lending Library, 1841’ and because of the context of the 1840 bible seems to have been made available to the village under the influence of Adela Knight.

13. The Holy Bible, containing the Old and New Testaments: translated out of the original tongues; and with the former translations diligently compared and revised / by his Majesty's special command. Appointed to be read in churches. Cum privilegio. (1840). Cambridge: Printed by John W. Parker, University Printer; and for the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London. [Accession no. 9485] Labelled ‘Chawton House, Blue Room’ and dates from the time of Edward Knight’s marriage to Adela Portal.

14. The Holy Bible, containing the Old and New Testaments: translated out of the original tongues; and with the former translations diligently compared and revised / by his Majesty's special command. Appointed to be read in churches. Cum privilegio. (1839). Cambridge: Printed by John W. Parker, University Printer; and for the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London. [Accession no. 9487] Bound similarly to the 1840 bible this is labelled ‘Chawton House, Green Dressing Room’ and is a partner to the ‘Blue Room Bible’.

15. Girdlestone, C. (ed.) The Old Testament. With a commentary consisting of short lectures for the daily use of families by the Rev. Charles Girdlestone M.A. vicar of Sedgley, Staffordshire (1837). London: Printed for J. G. & F. Rivington. [Accession no. 9477]

16. Girdlestone, C. (ed.) The New Testament of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ. With a commentary consisting of short lectures for the daily use of families by the Rev. Charles Girdlestone M.A. vicar of Sedgley, Staffordshire (1835). London: Printed for J. G. & F. Rivington. [Accession no. 9476]

Both of the Girdlestone testaments contain the bookplate of Montagu Knight.

17. Scott, T. (ed.) (1835) The Holy Bible containing the Old and New Testaments, according to the authorized version; with explanatory notes, practical observations, and copious marginal references / by Thomas Scott, Rector of Aston Sandford, Bucks. New edn. with the author's last corrections and improvements; and with two maps London: Printed for L. B. Seeley and Sons; Hatchard and Son; Baldwin and Cradock; and R. B. Seeley and Burnside. [Accession no. 9474]

18. The Holy Bible, containing the Old and New Testament / translated out of the original tongues and with the former translations diligently compared and revised, by His Majesty’s special command; appointed to be read in churches (1833). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

19. D'Oyly, G. and Mant, R. (eds.) (1826) The Holy Bible, according to the authorized version; with notes, explanatory and practical taken principally from the most eminent writers of the United Church of England and Ireland: together with appropriate introductions, tables, indexes, maps and plans / prepared and arranged by the Rev. George D'Oyly and the Rev. Richard Mant... under the direction of the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, for the use of families. Oxford: Printed for the Society at the Clarendon Press. [Accession no. 9468] This bible contains the bookplate of Edward Knight and lists, as traditionally for a family bible, Edward Knight’s marriage to Adela Portal, his second wife, and the details of their children, including Montagu Knight. This seems to confirm that the ‘Edward Knight’ bookplate found in the Knight Collection is not that of Edward Austen Knight as may have been thought. It also appears that the first leaf has been removed and this may have recorded the details of Edward Jnr.’s first marriage to Mary Dorothea Knatchbull.

20. La Bible qui est toute la Ste. Ecriture du Vieil et du Nouveau Testament autrement L'Ancienne et la Nouvelle Alliance (1678) .Amsterdam: chez la Veuve de Schippers. [Accession no. 9479] Contains Montagu Knight’s bookplate.

21. Cranmer, T. (1585) The Holy Byble, conteining the Olde Testament and the New. Authorised and appointed to be read in churches. Imprinted at London: By Christopher Barker, printer to the Queen's most excellent Maiestie. [Accession no. 8962] contains the bookplate of Montagu Knight.

22. Il Nvovo Ed Eterno Testamento Di Giesv Christo (1556). Lione: Per Giouanni di Tornes e Guillelmo Gazeio. [Accession no. 9480] Contains the bookplate of Montagu Knight.

The next step now is to see which of these can be found in both the 1818 and 1908 catalogues and to see what conclusions can be drawn from this evidence. Were the oldest bibles owned by the Knight family at the time of their publication, or purchased by Montagu Knight? There is a huge preponderance of bibles published from the 1830s and those of the sixteenth century contain Montagu Knight’s bookplate and it may be useful to look further at the influence of the Oxford Movement, and Anglo-Catholicism on Adela Knight, and subsequently her son.

Wednesday, 9 November 2011

Monday, 20 June 2011

‘But the woods are fine, and there is a stream’: Chawton House Library, gardens, landscape and books.

Chawton House Library’s main mission is to promote early modern women’s writing as such there is a wealth of material that places women’s writing of the period in context. Garden history considers aesthetic expressions of beauty through art and nature but it can also express an individual’s status or national pride. I took as my title a quote from Austen’s Mansfield Park because Mr Rushworth can only see himself in relation to his material possessions; one of which is his garden. Rushworth refers to Repton and the collection contains an edition of Repton’s Landscape Gardening, as revised by Loudon.

The production of books relevant to gardens and gardening begins historically with herbals. Herbals are a collection of descriptions put together for medicinal purposes and by the late-seventeenth century had to some extent become reference manuals for plant identification, relying on direct observation. The herbals in the collection seem to be logical starting point historically and this article considers a few of those to be found in the Library’s holdings but many more can be identified by referring to the online catalogue, available through the website:

http://www.chawtonhouse.org/

The striking herbal of Elizabeth Blackwell is one that is particularly poignant as part of the collection at Chawton House Library because of the convergence of Blackwell’s life and work: the need to make money and the use of her talents in doing so. She is an example of many women in the collection who wrote to survive financially and who managed to do so because of their intelligence and talent:

A curious herbal, containing five hundred cuts, of the most useful plants, which are now used in the practice of physic. Engraved on folio copper plates, after drawings taken from the life. By Elizabeth Blackwell (1737).

Elizabeth Blackwell (bap. 1707, d. 1758) was a botanical author and artist and her husband Alexander Blackwell used her dowry to establish a printing business in London, near the Strand. The business foundered and by 1734 he was incarcerated in the debtors’ prison. Blackwell extricated her husband from his difficulties with her reproductions of medicinal plants. She took lodgings in Swan Walk, Chelsea, close to the botanical garden where she found the living models for her botanical drawings. This text is an early issue with over half the plates coloured by a nineteenth-century hand.

Alongside this are later books of botany produced by Frances Arabella Rowden, Mary Lawrance, Jane Marcet and Mary Roberts. These works are primarily educational and highlight how the natural sciences were both being taught and what was seen an acceptable branch of science for women.

1. A poetical introduction to the study of botany. By Frances Arabella Rowden (1801).

Frances Arabella Rowden (1774-1840?) was a schoolmistress and poet, born in London, and initially educated by her aunt in Henley-on-Thames. In 1792 she entered the same school Austen attended, the forerunner of today’s Abbey School in Reading. This text comprises an exhaustive botanical classification interspersed with lush poems resonant with the chaste yearnings of her own young pupils, which included Mary Russell Mitford and Lady Caroline Lamb, also authors included in the collections at Chawton House Library.

2. Sketches of flowers from nature. By Mary Lawrance, teacher of botanical drawing, No. 86, Queen Ann-Street East, Portland-Place (1801).

Mary Lawrance (1794-1830) was a flower painter who first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1795. The text Sketches of nature was first published in 1801. In 1804 she was known to be giving botanical drawing lessons at ½ a guinea a lesson and a guinea entrance.

3. Conversations on botany, Jane Marcet (Sarah Mary Fitton and Elizabeth Fitton) (1818).

Jane Marcet (1769-1858) was a writer on science and political economy. Her wealthy and comfortable parents respected her intellectual curiosity and encouraged her as an intelligent thinker. She married Alexander Marcet, a physiological chemist, in 1799 and together they entertained some of the most distinguished scientists and thinkers of their time. She was a friend of Maria Edgeworth, Sir Humphry Davy and Michael Faraday. Marcet was depressive and she found relief in hard and useful work, which was encouraged by her husband, and her educational texts became the bulk of her literary output.

4. The wonders of the vegetable kingdom displayed. In a series of letters. By the author of ‘Select female biography,’ Mary Roberts (1822).

Mary Roberts (1788-1864) was raised a Quaker, and with her family later followed Joanna Southcott’s millenarianism. She wrote religious works as well as books about natural history. Wonders of the vegetal kingdom as an earlier example of her work had an observational freshness that was lacking in her later work which often sought to show the attributes of God through the natural world he created. I suggest, without the time for further research, that she was uncomfortable with the assessments emerging from contemporary scientific observation.

Current critical works examining the relationship of women to science in the collection are held in the post-1900 collection and they reveal the analysis that has been made of women’s writing in this field during the long eighteenth century:

1. Botany, sexuality and women’s writing 1760-1830: from modest shoot to forward plant, Sam George (2007).

2. The scientific lady: a social history of women’s scientific interests 1520-1918, Patricia Phillips (1990).

As well as herbals and botanical reference books the collections at Chawton House Library contain books about landscaping and gardening. Returning to Rushworth in Mansfield Park, the landscaping of a landowner’s property could indicate both his wealth and his place as a man of fashion, and Repton is the name bandied about by Rushworth.

The landscape gardening and landscape architecture of the late Humphry Repton, esq. being his entire works on these subjects. A new edition: with an historical and scientific introduction … by J. C. Loudon (1840).

Humphry Repton (1752-1818) was a landscape gardener who was originally apprenticed to an East Anglian textile manufacturer. After his parents’ deaths he became a gentleman amateur, taking a tenancy on Old Hall, Sustead, and spent his time reading, writing, drawing and improving his small farm. After he no longer had the money to support this life he used his abilities as a sketcher and writer to become a professional landscape gardener. He secured wealthy clients, presented himself as the ‘heir’ to Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, although he never took on the same scale of work, but established his reputation through writing. In this respect he addressed the increasing alignment of landscape and architecture. Loudon did what Repton, the snob, did not wish to do and that was to publish a cheaper edition of his work, while double-handedly inviting criticism of Repton and at the same time utilising the popularity of his ideas.

Chawton House was not exempt from its owners’ requirements for the fashions of the times, as we can see from the gardens around us today: from Edward Knight’s walled garden to the later additions requisite for the Repton-esque landscaped grounds and the Lutyens-inspired Library Terrace. The Knight Collection at Chawton House Library contains a very different book to Repton’s:

Abercrombie’s practical gardener, or improved system of modern horticulture; adapted to either small or large gardens: designed to assist those gentleman who manage their own gardens. (1823).

John Abercrombie (1726-1806), the son of an Edinburgh market gardener, was a horticulturist and writer. After attending the Grammar School, he first worked for his father and about 1750 he was employed at the Royal Botanic Garden, Kew, then at Leicester House. He worked for nearly twenty years as a gardener for the wealthy and his clients included the botanist William Munro. He subsequently ran his own market gardens and published his first book on practical gardening in 1767.

The fashionable garden could be created at the right price for men like Mr Rushworth and this commodification of the elements of landscape and the natural world are discussed further in some of the Library’s acquisitions of recent research:

1. Luxury and pleasure in eighteenth-century Britain, Maxine Berg (2007).

2. Luxury in the eighteenth century: debates, desires and delectable goods, edited by Maxine Berg and Elizabeth Eger (2003).

3. The consumption of culture 1600-1800: image, object, text, edited by Ann Bermingham and John Brewer (1995).

A garden was one prized luxury good in the eighteenth century and many others: porcelain, lacquer-ware, and textiles, traded by merchant companies posted out in India and the Far East were adapted for the European market by including the landscapes, images and from the natural world – such as flowers – popular at that time. Again to illustrate some of the breadth of the collection there are books that consider these aspects of eighteenth-century life and create context for the main collection, the books, not exclusively by women, dating from 1600-1830:

1. Chintz: Indian textiles for the West, Rosemary Crill (2008).

2. Authentic décor: the domestic interior 1620-1920, Peter Thornton (1984).

The production of books relevant to gardens and gardening begins historically with herbals. Herbals are a collection of descriptions put together for medicinal purposes and by the late-seventeenth century had to some extent become reference manuals for plant identification, relying on direct observation. The herbals in the collection seem to be logical starting point historically and this article considers a few of those to be found in the Library’s holdings but many more can be identified by referring to the online catalogue, available through the website:

http://www.chawtonhouse.org/

The striking herbal of Elizabeth Blackwell is one that is particularly poignant as part of the collection at Chawton House Library because of the convergence of Blackwell’s life and work: the need to make money and the use of her talents in doing so. She is an example of many women in the collection who wrote to survive financially and who managed to do so because of their intelligence and talent:

A curious herbal, containing five hundred cuts, of the most useful plants, which are now used in the practice of physic. Engraved on folio copper plates, after drawings taken from the life. By Elizabeth Blackwell (1737).

Elizabeth Blackwell (bap. 1707, d. 1758) was a botanical author and artist and her husband Alexander Blackwell used her dowry to establish a printing business in London, near the Strand. The business foundered and by 1734 he was incarcerated in the debtors’ prison. Blackwell extricated her husband from his difficulties with her reproductions of medicinal plants. She took lodgings in Swan Walk, Chelsea, close to the botanical garden where she found the living models for her botanical drawings. This text is an early issue with over half the plates coloured by a nineteenth-century hand.

Alongside this are later books of botany produced by Frances Arabella Rowden, Mary Lawrance, Jane Marcet and Mary Roberts. These works are primarily educational and highlight how the natural sciences were both being taught and what was seen an acceptable branch of science for women.

1. A poetical introduction to the study of botany. By Frances Arabella Rowden (1801).

Frances Arabella Rowden (1774-1840?) was a schoolmistress and poet, born in London, and initially educated by her aunt in Henley-on-Thames. In 1792 she entered the same school Austen attended, the forerunner of today’s Abbey School in Reading. This text comprises an exhaustive botanical classification interspersed with lush poems resonant with the chaste yearnings of her own young pupils, which included Mary Russell Mitford and Lady Caroline Lamb, also authors included in the collections at Chawton House Library.

2. Sketches of flowers from nature. By Mary Lawrance, teacher of botanical drawing, No. 86, Queen Ann-Street East, Portland-Place (1801).

Mary Lawrance (1794-1830) was a flower painter who first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1795. The text Sketches of nature was first published in 1801. In 1804 she was known to be giving botanical drawing lessons at ½ a guinea a lesson and a guinea entrance.

3. Conversations on botany, Jane Marcet (Sarah Mary Fitton and Elizabeth Fitton) (1818).

Jane Marcet (1769-1858) was a writer on science and political economy. Her wealthy and comfortable parents respected her intellectual curiosity and encouraged her as an intelligent thinker. She married Alexander Marcet, a physiological chemist, in 1799 and together they entertained some of the most distinguished scientists and thinkers of their time. She was a friend of Maria Edgeworth, Sir Humphry Davy and Michael Faraday. Marcet was depressive and she found relief in hard and useful work, which was encouraged by her husband, and her educational texts became the bulk of her literary output.

4. The wonders of the vegetable kingdom displayed. In a series of letters. By the author of ‘Select female biography,’ Mary Roberts (1822).

Mary Roberts (1788-1864) was raised a Quaker, and with her family later followed Joanna Southcott’s millenarianism. She wrote religious works as well as books about natural history. Wonders of the vegetal kingdom as an earlier example of her work had an observational freshness that was lacking in her later work which often sought to show the attributes of God through the natural world he created. I suggest, without the time for further research, that she was uncomfortable with the assessments emerging from contemporary scientific observation.

Current critical works examining the relationship of women to science in the collection are held in the post-1900 collection and they reveal the analysis that has been made of women’s writing in this field during the long eighteenth century:

1. Botany, sexuality and women’s writing 1760-1830: from modest shoot to forward plant, Sam George (2007).

2. The scientific lady: a social history of women’s scientific interests 1520-1918, Patricia Phillips (1990).

As well as herbals and botanical reference books the collections at Chawton House Library contain books about landscaping and gardening. Returning to Rushworth in Mansfield Park, the landscaping of a landowner’s property could indicate both his wealth and his place as a man of fashion, and Repton is the name bandied about by Rushworth.

The landscape gardening and landscape architecture of the late Humphry Repton, esq. being his entire works on these subjects. A new edition: with an historical and scientific introduction … by J. C. Loudon (1840).

Humphry Repton (1752-1818) was a landscape gardener who was originally apprenticed to an East Anglian textile manufacturer. After his parents’ deaths he became a gentleman amateur, taking a tenancy on Old Hall, Sustead, and spent his time reading, writing, drawing and improving his small farm. After he no longer had the money to support this life he used his abilities as a sketcher and writer to become a professional landscape gardener. He secured wealthy clients, presented himself as the ‘heir’ to Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, although he never took on the same scale of work, but established his reputation through writing. In this respect he addressed the increasing alignment of landscape and architecture. Loudon did what Repton, the snob, did not wish to do and that was to publish a cheaper edition of his work, while double-handedly inviting criticism of Repton and at the same time utilising the popularity of his ideas.

Chawton House was not exempt from its owners’ requirements for the fashions of the times, as we can see from the gardens around us today: from Edward Knight’s walled garden to the later additions requisite for the Repton-esque landscaped grounds and the Lutyens-inspired Library Terrace. The Knight Collection at Chawton House Library contains a very different book to Repton’s:

Abercrombie’s practical gardener, or improved system of modern horticulture; adapted to either small or large gardens: designed to assist those gentleman who manage their own gardens. (1823).

John Abercrombie (1726-1806), the son of an Edinburgh market gardener, was a horticulturist and writer. After attending the Grammar School, he first worked for his father and about 1750 he was employed at the Royal Botanic Garden, Kew, then at Leicester House. He worked for nearly twenty years as a gardener for the wealthy and his clients included the botanist William Munro. He subsequently ran his own market gardens and published his first book on practical gardening in 1767.

The fashionable garden could be created at the right price for men like Mr Rushworth and this commodification of the elements of landscape and the natural world are discussed further in some of the Library’s acquisitions of recent research:

1. Luxury and pleasure in eighteenth-century Britain, Maxine Berg (2007).

2. Luxury in the eighteenth century: debates, desires and delectable goods, edited by Maxine Berg and Elizabeth Eger (2003).

3. The consumption of culture 1600-1800: image, object, text, edited by Ann Bermingham and John Brewer (1995).

A garden was one prized luxury good in the eighteenth century and many others: porcelain, lacquer-ware, and textiles, traded by merchant companies posted out in India and the Far East were adapted for the European market by including the landscapes, images and from the natural world – such as flowers – popular at that time. Again to illustrate some of the breadth of the collection there are books that consider these aspects of eighteenth-century life and create context for the main collection, the books, not exclusively by women, dating from 1600-1830:

1. Chintz: Indian textiles for the West, Rosemary Crill (2008).

2. Authentic décor: the domestic interior 1620-1920, Peter Thornton (1984).

Wednesday, 13 April 2011

A Bold Stroke for a Theatre Company

Last Friday, a few employees from Chawton House Library took a trip to The Theatre Royal (http://secure.theatreroyal.org/PEO/site/home/index.php?), Bury St. Edmunds, to tour the beautiful Georgian theatre and watch a production of Hannah Cowley's 'A Bold Stroke for a Husband'.

The play was highly entertaining and I would thoroughly recommend the Little Bear Theatre Company - Hannah Cowley would have been proud! Have a look at their website for future productions http://www.littlebeartheatre.com/ and more information about them.

We have been reading 18th century female playwrights, including Misses Cowley and Pix, in the Chawton House Library monthly reading group and have discussed how well they would translate for a modern audience. I was happy for us to be proved right. Surely the success of this adaptation will encourage more theatre companies to produce the plays of these highly talented, but often forgotten, women.

The play was highly entertaining and I would thoroughly recommend the Little Bear Theatre Company - Hannah Cowley would have been proud! Have a look at their website for future productions http://www.littlebeartheatre.com/ and more information about them.

We have been reading 18th century female playwrights, including Misses Cowley and Pix, in the Chawton House Library monthly reading group and have discussed how well they would translate for a modern audience. I was happy for us to be proved right. Surely the success of this adaptation will encourage more theatre companies to produce the plays of these highly talented, but often forgotten, women.

Tuesday, 8 February 2011

Birth of the British Novel

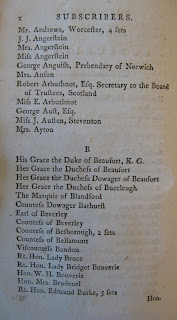

Henry Hitchings was filmed at Chawton House Library talking about Frances Burney with Emma Clery, Professor of Eighteenth Century Studies, University of Southampton. The page of subscribers from Camilla featuring Jane Austen referred to during the filming is the illustration above. You can see the programme using the following URL for another 6 days:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00ydj1p

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00ydj1p

Labels:

BBC,

Camilla,

Frances Burney,

Henry Hitchings,

Jane Austen,

novels

Saturday, 15 January 2011

Mary Delany inspring fashion

The dramatic art of Mary Delany with black backgrounds and vibrant colours continues to inspire fashion, as featured on the blog Peak of Chic:

http://thepeakofchic.blogspot.com/2011/01/mrs-delany-still-fashionable-centuries.html

http://thepeakofchic.blogspot.com/2011/01/mrs-delany-still-fashionable-centuries.html

Labels:

art,

fashion,

Mary Delany,

paintings

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)